I watched the last twenty laps of the 2024 Indianapolis 500 the old-fashioned way – from the infield, with a view of the exit of Turn 1. As the laps wound down, I walked a little closer to the exit tunnel, no longer within sight of the big screen TV that was playing out the action to the grandstands, nor able to hear the track PA. I could see the cars flash past for 4-5 seconds through the south short chute, but the only clue I had to who might be out front next time around was the sound of the crowd lining Turns 1 and 2 of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

From what I could hear and subsequently see, a huge roar went up whenever Alexander Rossi or especially Pato O’Ward took the lead. Conversely, there was a much more muted reaction – was it a collective groan? – every time Josef Newgarden came by in front. After the last of the quiet waves, the cars came around slowly with Newgarden in front, and I presumed that it was for a caution at the other end of the track. But no, Newgarden had actually won the race, and the crowd seemed…underwhelmed.

Walking through the tunnel and out onto 16th Street, the immediate post-race atmosphere was more subdued than I can ever recall, having experienced it from a variety of perspectives since 1978. Nobody was really talking about the finish or the race, despite it being what many are calling an instant classic. Maybe it was the late hour; the four-hour rain delay pushed the finish to nearly 8 p.m., and perhaps people were just eager to get home, dreading the traffic snarl they knew awaited them. But outside the Speedway, anyway, there just didn’t seem to be much post-race buzz. The few folks who were talking about racing were discussing the cheating scandal that earlier this year embroiled Team Penske and especially Newgarden, who was stripped of his victory in the season-opening St. Petersburg Grand Prix for illegally using his car’s “push to pass” function during restarts.

You probably remember that mess. IndyCar mistakenly identified during the pre-race warm-up at Long Beach that the three Penske cars driven by Newgarden, Scott McLaughlin, and Will Power, had access to push to pass at a time when the system was not supposed to be functioning. Subsequent research indicated that Newgarden and McLaughlin used the P2P illegally during the St. Pete GP, resulting in both drivers being DQ’d weeks after the fact. Newgarden’s offense was far more egregious than McLaughlin’s, and Power did not illegally use the button at all. He was docked a points penalty; four key team members, including Team Penske President Tim Cindric, were suspended from IndyCar activity during the month of May at Indianapolis, and the team was fined $75,000 and forfeited about $100,000 in prize money. A team statement blamed the situation on “significant failures in our processes and internal communications.”

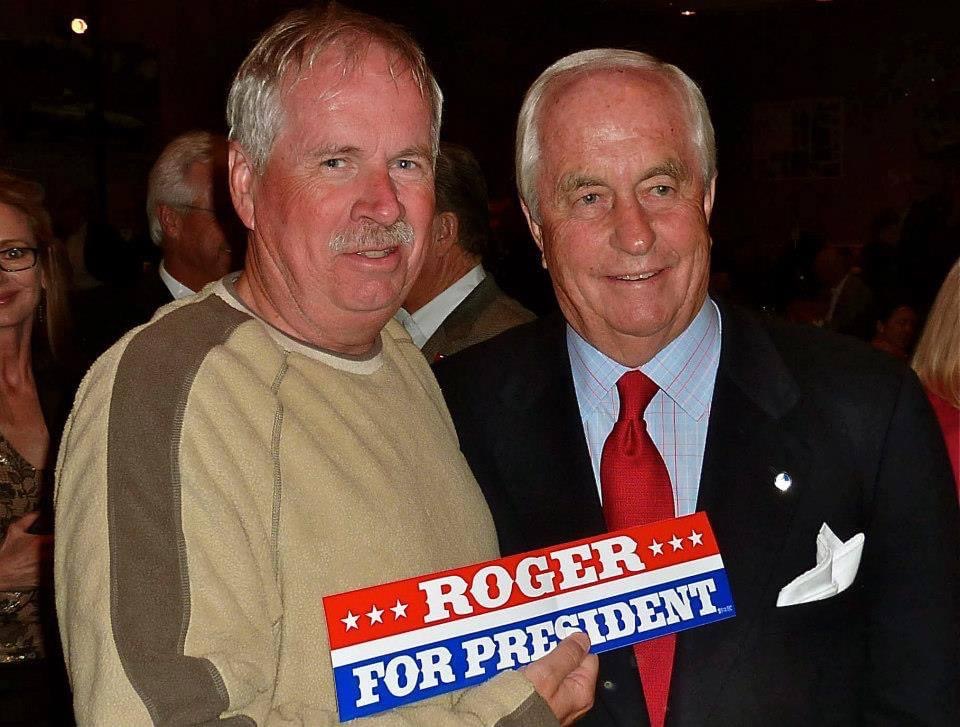

Roger Penske’s racing team has always sailed close to the wind and tempted fate with the rulemakers, going back more than 70 years to when he converted a Cooper Formula 1 car into a two-seat (allegedly) sports car called the Zerex Special. How about the acid-dipped late ‘60s Trans-Am cars? Mark Donohue, the driver associated with most of Team Penske’s early success, often talked about chasing an ‘unfair advantage;’ just how far will the modern Team Penske go in that pursuit?

Those days were mostly long forgotten. Until recently, given the team’s pedigree and resources, nobody questioned Team Penske’s consistent excellence and success on the track. But that was before Joey Logano created a webbed glove that he held out the window to gain an aerodynamic advantage during NASCAR Cup qualifying at Atlanta in February. That was before Team Penske’s illegal use of P2P at St. Pete in March, and another six weeks passed before that circumvention of the rules was discovered and revealed.

These are complicated times for Indy car racing; maybe “conflicted” is a better description, given that Roger Penske’s many conflicts of interest have finally caught up with him and now create a huge credibility problem for the sport that he quite literally owns.

Penske had a lot of hats to wear for the victory photos to commemorate his record-extending 20th Indianapolis win, his second consecutive with Newgarden:

Team Penske owner

Ilmor Engineering co-owner (with Mario Illien)

IndyCar Series owner

Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner

By all accounts, it was a thrilling race. It even generated television ratings up 8 percent year-on-year at a time when the IndyCar Series needs every eyeball it can reach. But given the way the race was resolved in Newgarden and Penske’s favor, the lack of buzz in the crowd suggests that the hangover from the P2P cheating scandal isn’t going to go away anytime soon.

There’s a strong feeling both within the paddock and amongst the fanbase that the Penske empire holds much too much power in the overall IndyCar equation. The penalties from IndyCar (owned by Penske) assessed against Team Penske (owned by Penske) but not against the Ilmor/Chevrolet engine program (co-owned by Penske) are widely seen as one branch of the Penske family tree lightly slapping the wrist of another.

Team Penske’s handling of the matter made things even worse in terms of public perception. Cindric blamed it on a line of code accidentally left in software written for IndyCar hybrid component testing in Summer 2023 and swears it wasn’t on the cars or used any earlier – like, say, twelve months ago, when Newgarden powered past Marcus Ericsson in a one-lap shootout to win the 2023 Indianapolis 500. Let’s not even get into the controversial and unprecedented red flag(s) that created the circumstances for Newgarden’s first Indy win…

Now he has two, but Josef Newgarden isn’t the flawless Golden Boy he was perceived as just twelve months ago. It’s hard to think of a reputation that has fallen faster, as Newgarden put himself at odds with many of his fellow drivers, even including his teammates. The breakup with his media marketing ‘Bus Bros’ partner McLaughlin was stunningly public, and McLaughlin seems as affable as bloke can be. Newgarden’s chest-baring six-pack exhibition on the ‘100 Days to Indy’ docuseries was soundly ridiculed, and many fans and competitors now think of him as arrogant and aloof. His tearful explanation that he didn’t understand the push-to-pass rules at St. Pete and Long Beach because he was allowed to use it all the time in the exhibition event at Thermal was met with universal disbelief. Newgarden has become IndyCar’s resident villain, and unlike Denny Hamlin, he did it without really trying.

While the IndyCar arm of the Penske conglomerate should be applauded for having the courage to air Team Penske’s dirty laundry in public and assess a light penalty, no one will ever truly know exactly how long Team Penske was illegally using push to pass before a fluke accident caused them to be caught. If it took a mistake by IndyCar to discover this covert violation by Team Penske, what will the next mistake reveal?

The calls for Roger Penske to divest himself from either his race team or the IndyCar Series have grown stronger and louder. Obviously, RP is not going to give up his pride and joy – the team. But there’s a rising belief that while the Indianapolis Motor Speedway looks great and the Indy 500 glides along like always, the series itself is being badly mismanaged under the guise of Penske Entertainment. In particular, the lack of alacrity in replacing a car and engine package now in its 13th season of competition is a remarkable failure for a series that boasts about engineering excellence and innovation.

Indianapolis Motor Speedway President Doug Boles was recently quoted in the Chicago Tribune, saying “70 percent of our fans don’t watch another race all year long.” That shows that IMS is doing a remarkable job of creating ‘place fan’ loyalty, but it’s truly alarming that IndyCar is not turning them into ‘race fans’ who will travel to events at Iowa or Detroit or tune into Laguna Seca or Nashville on TV. Fun fact: there were more people on the IMS grounds Sunday for the Indianapolis 500 than USA Network TV viewers nationally for the Long Beach Grand Prix, billed as an IndyCar crown jewel.

Penske Entertainment’s near total focus on IMS and the Indy 500 while the rest of the series falters is reminiscent of the circumstances in the late 1970s that prompted Roger Penske, Pat Patrick, and Dan Gurney to form CART to try to make Indy car racing a successful year-long entity rather than a Month of May phenomenon. It’s a shame that few lessons were learned from Indy car racing’s two ‘splits.’ Clearly, the Speedway and the Indy 500 are deeply personal for Mr. Penske, but Indy car racing, as a whole, seems to be just an expendable business. That attitude does not sit well with other Indy car team owners.

Embroiled in controversy and with Penske Entertainment’s management of the series under serious criticism, frankly, it’s a bad time for Team Penske to catch fire on the racetrack. But McLaughlin dominated at Barber, the first race after the P2P scandal broke, then Penske qualified 1-2-3 in high boost conditions for the Indianapolis 500, prompting more questions about the team’s ability to manipulate turbo-related software. The optics, as they say, are sub-optimal.

Now, of course, Penske owns his cherished 20th Indianapolis 500 triumph courtesy of Newgarden. It remains to be seen how this latest development settles in with an uneasy fan base that is starting to make noise about a lack of credibility on many levels – from Team Penske, from its drivers and leadership, and from IndyCar Series management. They say it’s time for greater separation between church and state.

But ultimately, this is Roger’s world. Love it or leave it.